2025. February 22. Saturday

Permanent Exhibition of the Painter József Horváth - Sopron

|

Address: 9400, Sopron Hátsókapu utca 2.

Phone number: (99) 312-326

E-mail: bertalan.horvath@archikon.hu

Opening hours: Thu-Sun 10-13, Sat 15-18

On prior notice (99/313-540) |

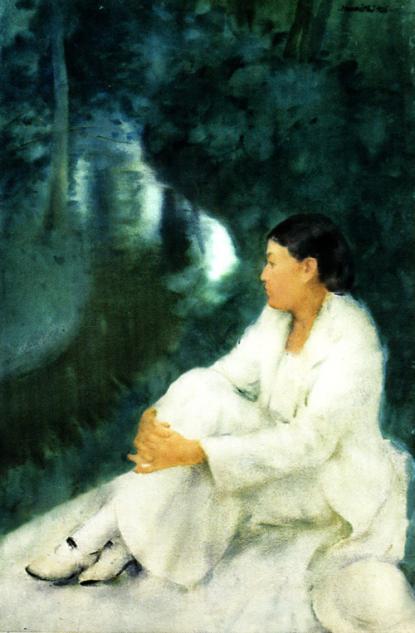

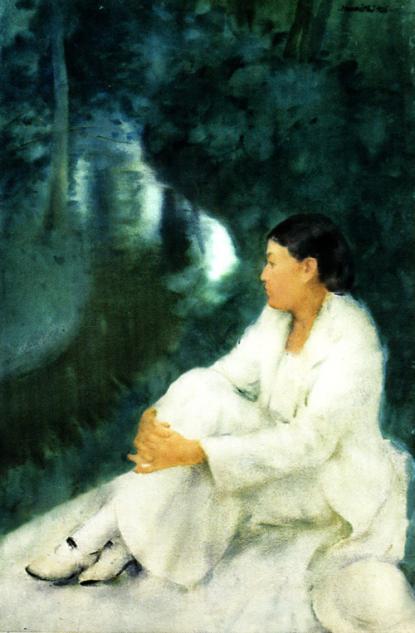

His painting was the imagination's and the brush's constant, persistent search for beauty. There are painters for whom Imagery is an intellectual struggle, and there are those for whom painting is a continuous conversation, the natural language of expression. Horvath was among the latter. This perhaps is one of the explanations for why his art has found its way into so many hearts.

But there was another magic to his painting: the masculine lyricism and emotional warmth that radiate from his works. Because in his art, it was not the style, but the passion that created it, which was important. Style is merely the painter's education, his means of carving out a niche for himself, the weaponry of enterprise. Every new enterprise creates new means of execution as well. This also explains the stylistic changes of different periods: every style lasts only until its secrets are divined. Those works, however, in which the emotional charge is particularly strong are not faced with this danger of passing. Horvath's pictures are like this.

The content is more interesting than the stylistic aspects of his works. He was interested in the language of art, not its grammar. The emotional content in Horvath's art speaks to us with the particular earnestness of his presentation. This relates to the artist's moral conduct, the reflection of which glitters in each of his works. One can look at his art and ask why his style lacks the magic of novelty, the astounding component that would truly provoke the viewer? But we can also ask where he got the courage to remain true to the great ideals that others had long since abandoned?

In his interpretation, art does not draw from the present to extract the new; rather it is reminiscence, the realisation of the completeness of the human spirit and the restoration of the wellbeing of the soul. He thought - rightly so - that art could neither contrive nor devise, but only continue, since it has been the natural form of expression for the human spirit for thousands of years. Art is an indulgence of the spirit, and it requires spirits who are fit for this indulgence. As likely as not, this was the thought that occupied József Horváth when he addressed the matter of the elite that understands art - and even his art.

Monet confessed that he painted the way birds sing, and Seurat was the first to emphasise theory and the importance of method. The development of modern style shows that painters had discovered a new truth: a hidden principle joins reality and artistic imagery. The effect is more artistic if the connection is sufficiently distant because then only the strong spark of imagination will be able to show through. With this discovery, however, the natural language of painting met its end and painters renounced the traditional, conventional style. Prior to this, it was the smoothly drifting gulf stream of the period's style that propelled them; but now this wind had died down beneath them, and everyone was forced to reach their goals using their own power.

However, followers of the new principle, the representatives of the avant-garde, were received with antipathy by those to whom they most liked to refer. The representative of the transformation of the modern natural sciences, Werner Heisenberg, who was one of the founders of today's quantum mechanics, said, "There is hardly reason to belive that the world view of the contemporary natural sciences could have directly influence the encounter the nature the artists of our age."

There is no indication in József Horváth's art that this traditional relationship between man and nature had changed at all. In his pictures, it's as if the grass, the trees, the hills and the waters were all speaking with human voices, the voice of pleasure, pain, love and ecstasy. He liked those works that showed signs of human emotionsand those phenomena that were particularly intense and gripping, through which nature appears intimately and with the wondrousness of mythology. He was a virtuoso of his chosen techniques. But is there art without virtuosity? Degas once said, "If you have a hundred thousand francs worth of craftsmanship, spend five sous to buy more."

Ferenc Sebestény

But there was another magic to his painting: the masculine lyricism and emotional warmth that radiate from his works. Because in his art, it was not the style, but the passion that created it, which was important. Style is merely the painter's education, his means of carving out a niche for himself, the weaponry of enterprise. Every new enterprise creates new means of execution as well. This also explains the stylistic changes of different periods: every style lasts only until its secrets are divined. Those works, however, in which the emotional charge is particularly strong are not faced with this danger of passing. Horvath's pictures are like this.

The content is more interesting than the stylistic aspects of his works. He was interested in the language of art, not its grammar. The emotional content in Horvath's art speaks to us with the particular earnestness of his presentation. This relates to the artist's moral conduct, the reflection of which glitters in each of his works. One can look at his art and ask why his style lacks the magic of novelty, the astounding component that would truly provoke the viewer? But we can also ask where he got the courage to remain true to the great ideals that others had long since abandoned?

In his interpretation, art does not draw from the present to extract the new; rather it is reminiscence, the realisation of the completeness of the human spirit and the restoration of the wellbeing of the soul. He thought - rightly so - that art could neither contrive nor devise, but only continue, since it has been the natural form of expression for the human spirit for thousands of years. Art is an indulgence of the spirit, and it requires spirits who are fit for this indulgence. As likely as not, this was the thought that occupied József Horváth when he addressed the matter of the elite that understands art - and even his art.

Monet confessed that he painted the way birds sing, and Seurat was the first to emphasise theory and the importance of method. The development of modern style shows that painters had discovered a new truth: a hidden principle joins reality and artistic imagery. The effect is more artistic if the connection is sufficiently distant because then only the strong spark of imagination will be able to show through. With this discovery, however, the natural language of painting met its end and painters renounced the traditional, conventional style. Prior to this, it was the smoothly drifting gulf stream of the period's style that propelled them; but now this wind had died down beneath them, and everyone was forced to reach their goals using their own power.

However, followers of the new principle, the representatives of the avant-garde, were received with antipathy by those to whom they most liked to refer. The representative of the transformation of the modern natural sciences, Werner Heisenberg, who was one of the founders of today's quantum mechanics, said, "There is hardly reason to belive that the world view of the contemporary natural sciences could have directly influence the encounter the nature the artists of our age."

There is no indication in József Horváth's art that this traditional relationship between man and nature had changed at all. In his pictures, it's as if the grass, the trees, the hills and the waters were all speaking with human voices, the voice of pleasure, pain, love and ecstasy. He liked those works that showed signs of human emotionsand those phenomena that were particularly intense and gripping, through which nature appears intimately and with the wondrousness of mythology. He was a virtuoso of his chosen techniques. But is there art without virtuosity? Degas once said, "If you have a hundred thousand francs worth of craftsmanship, spend five sous to buy more."

Ferenc Sebestény